When the rupee weakens, it doesn’t just move a chart – it shows up in prices, EMIs and your investment returns. Imported goods, foreign trips and overseas education start to feel more expensive, while exporters, gold and global funds often get a boost. This note breaks down, in plain English, what rupee depreciation is, why it happens, how concepts like REER and the IMF’s “crawl‑like” tag fit in, and what history says about the rupee’s long slide.

Currency depreciation is when your country’s currency, like the INR, loses value against another – like the USD – in a freely traded market. For example, if the rupee rate shifts from ₹75 to ₹82 per dollar, the rupee’s weakened – you now need more rupees to catch that same dollar for imports or travel.

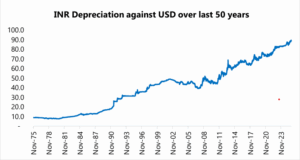

From ₹9 to ₹90: Rupee’s Half-Century Drop against USD

Source: Bloomberg, HDFC TRU; Note – Data as of 30th Nov 2025

The rupee has steadily lost value against the US dollar over the last 50 years, and the pace of depreciation has not been uniform across time.

The exchange rate has moved from single digits in the mid‑1970s to around 90 per dollar by 2025, showing a large, long‑term weakening of the rupee.

There are phases of sharp jumps (late 80s–early 90s, around 2013, and post‑2020), mixed with periods where the rupee is relatively stable for a few years.

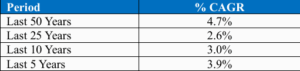

INR Depreciation against USD across various periods

Source: Bloomberg, HDFC TRU; Note – Data as of 30th Nov 2025

So far, this financial year, the rupee has slipped by close to 5% against the US dollar, hovering above 90-per-dollar mark (at the time of writing). In simple terms, you now need more rupees to buy the same dollar, which makes imports like oil, electronics, and foreign travel costlier.

The main culprits behind rupee depreciation are higher trade tariffs imposed by US on India, widening current account deficit, higher interest rates overseas pulling money out of India, our large import bill (especially oil and electronics), and foreign investors selling their Indian investments.

The Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) is a way of checking whether the rupee is “overpriced” or “cheap” compared to the currencies of India’s main trading partners after adjusting for inflation differences. Instead of looking only at USD/INR, REER takes a basket of currencies, weights them by how much India trades with each country, and then adjusts for how fast prices are rising in India versus abroad.

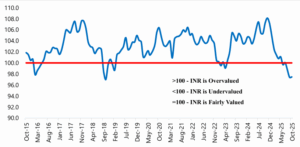

Recently, RBI data show that the rupee’s REER has dropped from a record high of about 108 in late 2024 to below 100 in 2025, meaning the rupee has moved from being overvalued to slightly undervalued, which broadly makes Indian exports more competitive while imports become relatively costlier.

Rupee REER Index – Rupee has recently moved to undervalued zone.

Source: Bloomberg, HDFC TRU

Over the last decade, the rupee has spent around 90% of the time above the REER fair‑value line of 100, i.e., in the “overvalued” zone.

Rupee REER has dipped into the undervalued zone during the last decade only four times, including now, and the previous three episodes were brief before the REER bounced back above 100.

The current move below 100 therefore suggests the rupee is relatively cheap by its own history, though past patterns also show such cheap phases have not lasted very long.

The IMF has recently said India now follows a “crawl-like arrangement” for the rupee, which is just a fancy way of saying the rupee is allowed to move gradually rather than being kept fixed or left completely free. In this setup, the exchange rate tends to stay within about 2% of a slowly moving trend for several months, so the rupee can weaken or strengthen bit by bit instead of through sudden big jumps.

For India, this means the RBI lets market forces push the rupee gently – often with a mild depreciation bias – while stepping in only to smooth sharp, chaotic moves, trying to balance stability for importers and borrowers with enough flexibility to handle global shocks.

For Indians putting money overseas, a weaker rupee can be a benefit for returns because whatever you earn in dollars, euros or pounds becomes more rupees when you bring it back home. For example, say your US equity fund gives 8% in USD over a year, and in the same period the rupee weakens 4% against the dollar – your rupee return is 12%, because you gain both from the US market return and from the currency depreciation.

History shows the rupee has lost around 4–5% per year on average against the dollar over the last 50 years and about 3–4% in recent years, so if that broad trend continues, long-term overseas investors could keep getting an extra currency kicker on top of market returns, even though the ride can be bumpy in the short term.